Illustration based on image by © enisakysoy / Thinkstock

At one level, the ideas and reality of sustainable development and liberal democracy overlap and are interdependent. Common to both sustainable development and democracy is inclusive and equitable participation – the ability of all people to come together and be involved in decisions about how we live and the goals we want to achieve as societies.

The justice, legitimacy and transparency achieved by democratic contests and safeguards make the achievement of sustainable development fairer and accepted. The survival of democracy will also be very difficult in an unequal, resource-constrained and overheated world. In other words, sustainable development itself is foundational to any democratic political system.

Any such discussion also has to take into account the role and power of the economic system in creating problems and opportunities for both sustainable development and democracy, as well as the increased complexity and uncertainty of the challenges facing humankind.

There are, however, tensions between the two systems of ideas and practices which need to be resolved if current political democratic systems are to adapt in order to better tackle the challenges of sustainable development and meet the needs of future generations. You can find out more about some of these tensions in our briefing paper Exploring the tensions: The relationship between democracy and sustainable development. They are also set out in the table below:

| Existing liberal democracies | Sustainable development |

| Tendency to short-term thinking, activity and policy design |

Greater focus on long-term impacts, intergenerational equity and environmental stewardship. |

| Dominant ethos of individual freedom | Collaborative ethos |

| Competition between ideas and political parties ensures pluralism, with no single vision of the ‘good life’ or how to get there | Shared goals to co-ordinate activities over time |

| Primary focus on representative government with relatively limited public and stakeholder participation | Emphasis on more extensive public and stakeholder participation and collective decision-making |

| Defined political geographies and legally defined citizens | Recognition that drivers and impacts cross political geographies, time, and levels of governance; affected parties include people in other political jurisdictions, future generations and nature |

| Economic growth seen as measure of success and way to deliver improved quality of life for citizens | Pursuit of individual and societal wellbeing emphasised – integrating economic, environmental and social considerations |

| Environmental limits not systematically taken into account | Environmental limits to economic and social activity |

| Decision-making divided into relatively discrete policy areas (such as health); use of socio-economic tools (eg cost-benefit analysis) for choice and resource allocation | Integrated and precautionary policy in recognition of complex and uncertain impacts and interactions; supported by multi-criteria decision-making tools |

This challenge is also part of the wider pressure on current models of democracy arising from the low levels of trust in democratic institutions and processes as well as increased political polarisation.

To more easily consider the innovations required, we can group parts of the overall challenge into several themes:

-

- Participation and accountability to improve decisions, implementation, justice and legitimacy.

- Political institutions and policy-making that incorporate sustainable development challenges and the long-term, better integrate decision-making across specific policy areas, and appropriately value and incorporate options, risk and uncertainty.

- Constitutions, rights and law which embed the long-term, nature, future generations and sustainable development principles.

- Promoting culture, values and awareness that create supportive norms, understanding and collaboration.

- The roles of civil society and business in adapting, being part of, and innovating democracy to address sustainable development.

We also gather Ideas in Action which illustrate the different ways that people are addressing these challenges

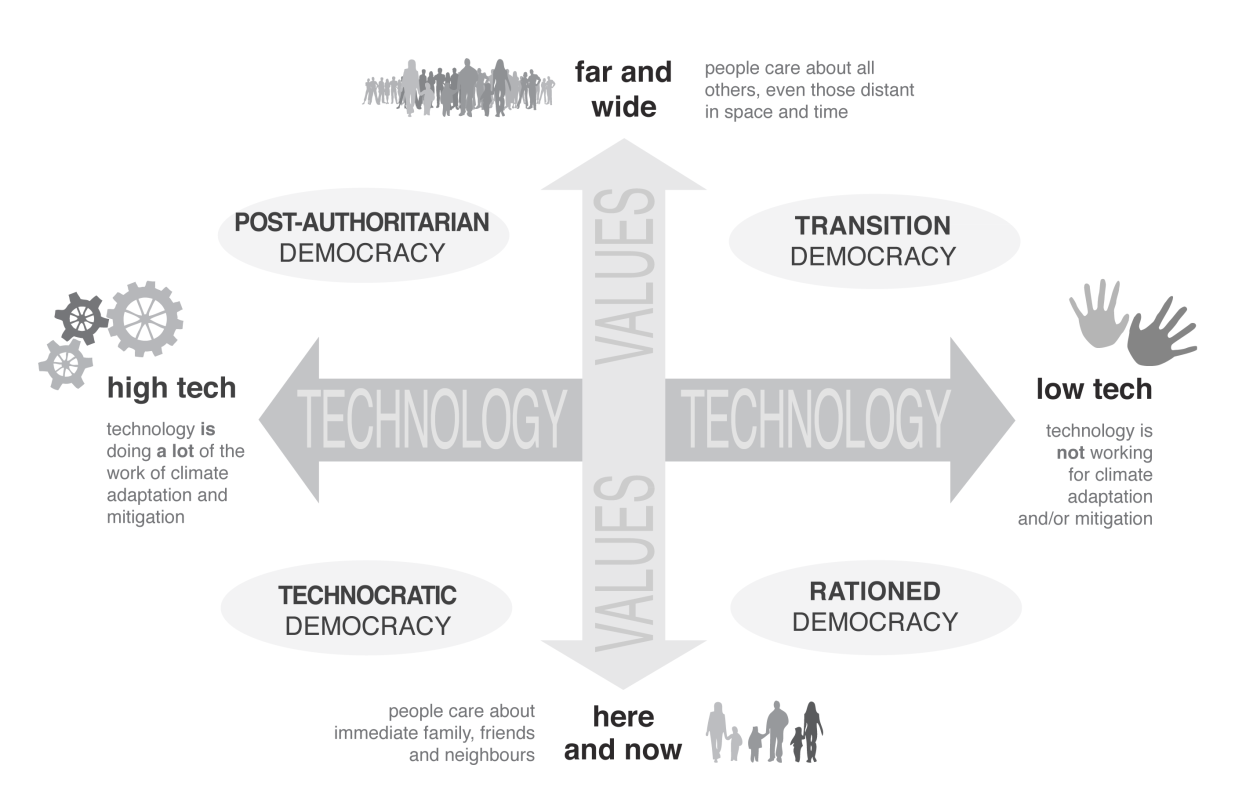

We first looked at these issues in relation to climate change between 2009 and 2012. ‘The Future of Democracy in the Face of Climate Change‘ was a series of five papers which culminated in four future scenarios to 2050: transition democracy, post-authoritarian democracy, technocratic democracy and rationed democracy (based on two uncertainties: nature and availability of technology, and values prevalent in society).

Since then our thinking has further developed to incorporate the wider scope of environmental sustainability and socio-economic wellbeing, and particularly the needs of future generations.